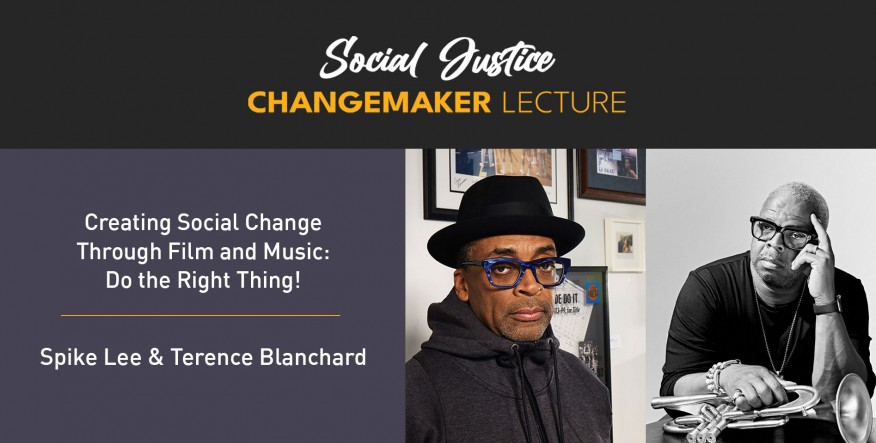

The School of Social Work presented Spike Lee and Terence Blanchard in the inaugural Social Justice Changemaker Lecture. Established by a generous gift from Neil and Annmarie Hawkins, parents of Rachel Hawkins, MSW ‘12, this new series brings prominent experts and advocates from multiple disciplines — including social sciences, science, humanities and the arts — to address pressing social justice issues.

“Today we celebrate the School of Social Work’s centennial birthday,” said Dean Lynn Videka. “We are absolutely thrilled to host this conversation. I want to thank Neil, Annmarie and Rachel Hawkins - for their gift that makes today’s changemaker lecture possible. The lecture series recognizes people, like Terence Blanchard and Spike Lee, who have created social change through their work, in order to inform and inspire the work of our students and faculty.”

“When you think about the first 100 years of Michigan Social Work, you think of the impact of all the students, alumni and faculty,” said Neil Hawkins. “That impact, that collective social impact has been enormous and powerful and lasting.”

In introductory remarks, MSW student Trey Gates shared the lasting influence of the arts in his own life. “While playing trumpet, I learned to manage my breathing and not to sweat the small stuff,” he said. And Robert Sellers, Vice Provost for Equity and Inclusion, and Chief Diversity Officer added his congratulations on the School’s Centennial. “Everyone in the U-M community can be proud of the school’s legacy,” he said. “Over the past century, the School has upheld the greatest qualities of U-M public mission: educating generations of social work leaders, advancing social justice and creating positive change.

This first lecture was a freewheeling, livestreamed conversation on the role of social justice in Lee and Blanchard’s collaborations — Blanchard has composed the score for more than 15 of Lee’s films. Robin R. Means Coleman, vice president and associate provost for diversity and inclusion, chief diversity officer and the Ida B. Wells and Ferdinand Barnett Professor in the Department of Communication Studies at Northwestern University and Daphne Watkins, University Diversity and Social Transformation Professor, director of the Vivian A. and James L. Curtis School of Social Work Center for Health Equity Research and Training, and Professor of Social Work moderated.

“If you’ve watched any previous interviews with Spike Lee and Terence Blanchard, then you know they don’t need any help from us in keeping the conversation going,” said Watkins by way of introduction. “I imagine that after three decades of work together, this may be more like a conversation between two friends.” And indeed, Lee and Blanchard discussed the importance of honoring the legacy of great Black artists and of developing craft. They also bantered and finished each other’s sentences in a discussion that included childhood memories, laughter, basketball references, along with advice for young artists and activists.

As children, both Lee and Blanchard were raised with an awareness of social justice issues. Lee’s family discussed current events around the dinner table. Blanchard was raised in a church that was socially conscious. “It made me realize that if I had a platform, I should use it to heal the sufferings and take away the pain of the oppressed if I could,” said Blanchard.

“The thing I like about Spike is that he doesn’t shy away from any topic, I do my best to help him tell stories, because these stories are important. ‘Chi-Raq’ was an effort to deal with the violence that was happening in Chicago,” explains Blanchard. “No one else wanted to tackle it, so Spike did it in a way that was artful and unique.”

But Lee shies away from defining his work in easy terms. “Labels are handcuffs,” said Lee, “I really try to stay away from labels because they can hinder you.”

Lee spoke from his office, the walls of which were covered with murals of legendary Black artists. He and Blanchard returned repeatedly to the theme that their work builds on the generations of Black Artists who came before them, and how the legacy of those artists inspires them to bring their “A” game at all times because they know that their work paves the way for the next generation. “We are blessed to be standing on top of strong shoulders,” said Blanchard. “It’s like being in that game with Michael Jordan - if they pass the ball to us, we can’t miss the shot.”

Blanchard mentioned that he is the first Black composer to have a work performed at the Metropolitan Opera. He asks “Do you think I’m the first qualified to have a work at the Met? No. It’s about who has been in the establishment and who has been in the audience, and opening up, as a society and a nation, to hear all voices.”

“Every so often, Hollywood rediscovers Black artistry,” said Lee. “Right now, we are the flavor of the month and we have to do everything we can to ensure it’s not a fad. Gatekeepers decide who is doing what and my focus is to get a gatekeeper to get us a seat at the table.”

The conversation included questions from U-M students, many of whom were concerned about how to manage their social justice work as artists. Lee’s advice: Don’t put yourself in compartments. “These beautiful minds are putting up limitations and fences that aren’t there. For me, it’s all filmmaking and storytelling.”

Blanchard added how he used his own personal experiences to score the opening speech in “Malcolm X.” “The percussion crash is my heartbeat, it’s the same thing I felt when I first heard Malcolm X as a child. You aren’t separating your personal life from any of it.”

Repeatedly, Lee and Blanchard stressed the importance of young artists focusing on their craft.

“You may have a great story to tell, but if you don’t have the skills and craft to communicate that story, you aren’t going to be successful,” Lee emphasized. “Overnight success is the biggest lie - there’s no such thing. It’s the work ethic and the commitment to your craft. If you aren’t able to do that, then you are cheating yourself and cheating your parents.”

“Do your best work, do what’s best for the project, do what’s best for the story, not what’s best for the artist” added Blanchard.

If you truly love what you are doing, you will have a thirst for everything about what you are trying to do,” summed up Lee. “If you don’t have the thirst, you aren’t thirsty.”

The recorded lecture is available to view on the School of Social Work website until Wednesday, May 7, and was presented in partnership with the College of Literature, Science and the Arts, the Office of the Provost, the Penny W. Stamps School of Art & Design, the School of Education, the School of Music, Theatre & Dance, and the University of Michigan Arts Initiative.