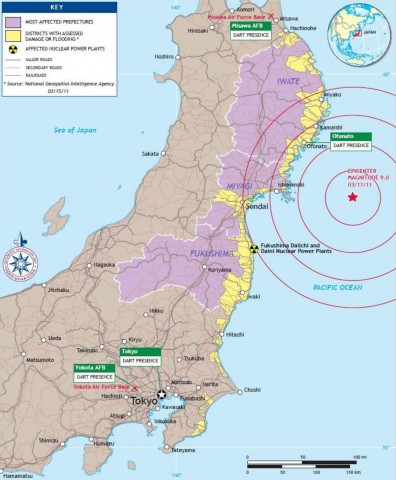

On March 11, 2011, a magnitude 9.0 earthquake, triggered massive tsunamis, which led to nuclear meltdowns and hydrogen explosions at the Fukushima Daiichi Power Plant in northeastern Japan. This unprecedented disaster called the Great East Japan Disaster, continues to cause far-reaching destruction to human lives and the environment. Incidents of violence against women and children following major disasters have been documented worldwide. After the Great East Japan Disaster, Professor Yoshihama contacted colleagues in Japan and established a national network to address women’s rights and welfare and she co-directed the network’s research committee and conducted action research projects with the goal of strengthening gender-informed disaster policies and responses in Japan

One such project is the study of gender-based violence following the disaster. This study, first of its kind in Japan, discovered a wide range of abuse and exploitation, including quid pro quo sexual assault, where threats were used to force compliance in exchange for shelter, food, and other life-sustaining resources. The study’s findings have been presented at international and national policy-oriented meetings, such as the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women and the Japanese Government Prime Minister’s Office, Gender Equity Bureau’s Disaster Prevention & Reconstruction Working Group. The Project reports are available in English and Japanese. The recent revisions to national and local disaster planning policies and plans acknowledge the risk of post-disaster gender-based violence. Changes at policy and societal levels are slow and require sustainable (and creative) advocacy efforts, but science and research play important roles. It is this type of engaged and transformative scholarship that Professor Yoshihama continues to engage in.

Professor Yoshihama is a licensed social worker and has worked with many women and families in both the U.S. and Japan. After the Great East Japan Disaster, the Gender Equality Bureau of the Japanese Prime Minister’s Office (equivalent of the U.S. President Office) invited her to train over 400 counselors on group work with disaster victims.

Gender-based violence after the disaster has remained virtually unrecognized and untold in Japan. Shortly after the 2011 Great East Japan Disaster, the National Police Agency, for example, issued a warning against the alleged “rumors” that rapes and other serious crimes had been committed in the disaster-affected areas; the Agency stated that as of April 1, 2011, no cases of rape or aggravated assault had been reported. In contrast, Professor Yoshihama and colleagues’ study documented various incidents of sexual assault, sexual harassment, and unwanted sexual contact perpetrated, many of which were targeted at women who were single, divorced, separated, or widowed. Perpetrators often exploited a sense of fear, helplessness, and powerlessness, including quid pro quo types of assault where threats were used to force compliance with sexual demands in exchange for shelter, food, and other life-sustaining resources. In addition, the study found incidents of domestic violence. In the vast majority of reported domestic violence cases, violence had begun prior to the Great East Japan Disasters. After the disasters, the violence continued or resumed, often with greater severity. While trauma and stress from the disasters undoubtedly affected the behavior of the perpetrators, trauma and stress do not cause violence. If they did, all disaster-affected individuals would perpetrate violence at an increased rate, regardless of gender. Yet, the perpetrators were overwhelmingly men even though both men and women were exposed to the disasters and its effects. Domestic violence is rooted in the very societal structure and ideology that perpetuate gender inequality of male domination and female subordination (Yoshihama, 2005). Study findings point to various ways in which the disasters intensified the risk and vulnerability of women and children to violence and harassment.

In the fall of 2016, a major national newspaper ran a one-month long article series on disaster and gender, and featured our study. Not only did the article report the atrocity of post-disaster gender-based violence, it also highlighted the importance of research that exposes hidden social problems. These responses mark a stark contrast to the previous silence or dismissal of the issue by the government and the media. Changes at policy and societal levels are slow and require sustainable (and creative) advocacy efforts, but science/research plays an important role. It is this type of engaged and transformative scholarship that Professor Yoshihama continues to engage in.