Aaron McNeece loved his time at the University of Michigan where he spent five years while earning his MSW (1971), and completing his PhD (1976).

“Once I completed a draft of my dissertation, we headed south as soon as we could,” McNeece explained. “We’re from the South and we were ready to return to our roots. We never got used to those long Michigan winters, especially with two housebound toddlers. I defended the dissertation a year later.”

Even though he and his family promptly returned to Arkansas (then Kentucky, and later Florida), McNeece has always had a special place in his heart for Michigan.

“I have two degrees from the University of Michigan that have opened doors for me throughout my career; those opportunities wouldn’t have been available to me otherwise.”

McNeece’s field placements with the House Sub-committee on Human Services in Lansing taught him an invaluable lesson.

“Two field placement experiences were a strong lesson that social workers can have an impact on public policy.”

During his field placement working with the Michigan House Sub-committee on Human Services, he wrote a report which helped close down the Lansing Boys Training School, because treatment of the boys was not in the best interest of the children. He saw firsthand the need for more guidelines regarding the treatment of the students.

“I’ve had an interest in juvenile justice ever since my field placement, McNeece said. Massachusetts led the way to reform juvenile justice in the 1970s, and I wanted Michigan to be right behind them to make improvements in their system.”

His second field experience led to a dramatic improvement with the distribution of food stamps.

“We did a study with the Michigan Food Stamp Program, which uncovered the humiliation recipients experienced while standing in long lines at the distribution centers located in banks. Women holding babies would stand for hours while passersby would shout out, ‘Get a job.’ There’s just no dignity in that.”

McNeece’s study certainly improved the situation in 1972 when Michigan became the first state to distribute food stamps through the U.S. Postal Service.

“Strong social work presence increasingly leads to more rational social policy, because social workers are at the frontline and know what’s happening with people.”

Throughout his career, McNeece focused on public policy and justice system issues. For the past 20 years, he’s been very interested in addiction, and chemical dependency, and more specifically the role substance abuse plays in crime and the justice system.

He was the director of the Institute for Health and Human Services Research at Florida State University from 1992 to 2001. He also served as a consultant to the U.S. Department of Justice on substance abuse issues, and to the Irish National Council on Alcoholism. For 30 years he provided research-based policy advice to both adult and juvenile justice agencies in Florida. In 2007 he was appointed to a Commission on Juvenile Justice Reform by the governor of Texas.

“More than 75 percent of the men incarcerated in Florida prisons were under the influence of drugs or alcohol at the time of their crime,” McNeece said.

“That’s an overwhelming statistic. And most of them continued abusing drugs or alcohol while in prison.”

“During my research while working in the justice system, there wasn’t a day that went by that we didn’t find drugs or alcohol inside a federal corrections institution,” McNeece said.

He reminisced that the biggest haul they found was six cases of Budweiser in an inmate’s cell. He admits that rivaled the still the inmates created in the exercise yard where they fermented moonshine with the compostable scraps from the dining hall…the tip off…a dramatic decrease in the garbage getting carried out of the kitchen.

His in-depth research into addiction issues resulted in more than 100 articles and books, and his latest publications have focused on the connection among drugs, crime, and public policy. Since 1989, he has conducted evaluations of approximately 130 criminal justice system programs.

The most gratifying time of his career was teaching graduate students at Florida State University. McNeece taught classes on subjects ranging from social welfare policy and administration to substance abuse and treatment, and criminal justice system issues.

“I never got as much pleasure out of anything else in my career as teaching graduate students.”

McNeece says it’s always gratifying to run into former students in professional positions all over the South. McNeece has been actively volunteering since he retired in 2008 as the dean of the College of Social Work at Florida State University.

When asked about his greatest challenge as dean, there was no hesitation with a response.

“My greatest challenge as a dean was keeping the school funded…Florida was always going through budget cuts, but then again, most schools have suffered budget cuts during this recession.”

As a result of his outstanding experience at U-M’s School of Social Work and his commitment to education, McNeece has established a scholarship to focus on non-profit administration, policy work and community organization. He created the C. Aaron McNeece and Sherrill McNeece Endowed Graduate Support Fund.

“I’d like this scholarship to go to someone who is in financial need and who has additional expenses for field placement,” McNeece said.

During his field placement, McNeece traveled to Lansing three times each week, and yet he didn’t need to work or take out loans because he had a scholarship that helped him with the additional expenses of having a long commute.

Strong social work presence increasingly leads to more rational social policy, because social workers are at the frontline and know what’s happening with people.

“I have a strong sense of obligation to pay back what I received from the University, and this scholarship is my way of paying it forward.”

When asked about retirement, he says that he is so busy now that he’s not sure how he managed to work in the job part of his life.

“There are some things I miss about working. Most of all, I miss teaching, but otherwise I’m busy all day long.”

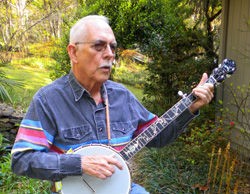

Since retiring, in addition to his volunteer work, he enjoys traveling with his family and playing the banjo, mandolin and guitar for an hour or two just about every day.

“I’ve been playing the banjo since I was nine years old. I’ve collected 10 banjos over the years, but my favorite is the 1911 Vega Whyte Laydie I bought in Ann Arbor in 1972; it sounds great!”