The forn,1ation of social groups is a naturally occurring part of human behavior. People group around common interests or experiences. Over time values, beliefs and behaviors emerge in the form of a culture. Having common features or a common history can lead to identification with the group. An immediate family or an entire country can constitute one's cultural group.

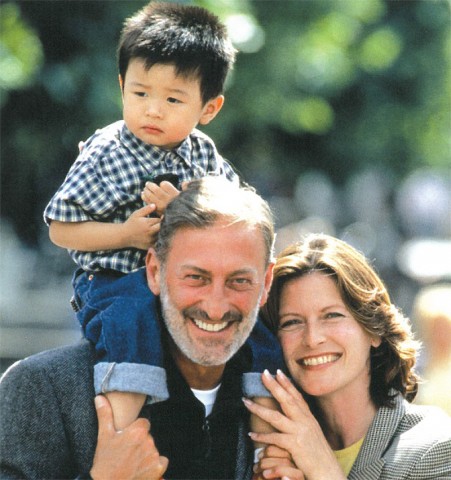

The existence of multiple cultures can be problematic when children from a less powerful group are adopted by adults from a more powerful one. It becomes easy to overlook or minimize the importance of the child's culture. Transracially or internationally adopted children bring with them a culture of origin, albeit a culture whose importance may be obscured by earlier experiences of abuse, neglect and severe poverty. Their culture takes on greater salience as they move into adolescence and young adulthood where the need to establish one's identity abounds.

Most social workers will provide services eventually to transculturally adoptive families or individuals. In 1996, 702,000 U.S. children lived with two adoptive parents (Fields, 2001). Domestic transracial adoptions traditionally have included African American children, biracial children and children of Hispanic origin. (Adoption and other child welfare services to Native American children are generally handled by the tribe with which their birth family is affiliated.) Certain knowledge of the experience of these families or individuals

is useful, regardless of the social worker's specialization area. Only fortyone percent of clinical practitioners responding to a vignette involving an adoptive family considered the family's adoptive status in their planning and intervention (Mitchell, 1991). While social workers are less likely to overlook differences in transcultural adoption because of physical differences among members, they should keep in mind that the experience may have different meanings for all involved.

There is no dependable estimate currently of the number of U.S. transracial adoptions occurring annually or of the total number of transracially adoptive families. The United States stopped collecting data on transracial adoptions in the early 1970s; data collection resumed in 1997 and data are being adjusted to fit the new categories for race and ethnicity in the 2000 Census.

In 2000, 18,120 children were adopted internationally by U.S. families (U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, 2001). The largest proportion came from Asia (48%), followed by children from Europe (38%), North America (10%), South America (3%) and Africa ( 1%). The largest proportion of Asian adopted children came from the People's Republic of China (57%) while children from Russia represented the largest percentage of European adopted children (60%). Sixty-five percent of all children internationally adopted in 2000 by U.S. families-78% of those from Asia, and 97% of those from the People's Republic of Chinawere female. Of the 702,000 children living with two adoptive parents in the United States in 1996, 13% were Asian and Pacific Islander although children from these regions made up only 4% of all children living in the United States (Fields, 2001 ).

Children not raised in their culture of origin may experience not belonging fully to either that culture or the majority culture. They may have physical features that connect them with natives of a particular culture but they don't speak the language or have other characteristics associated with the cultural group. Children adopted from Europe have no physical features to connect them with their country of origin, making it easy to assume that no attention to their culture is needed.

In an effort to socialize their children in the child's own culture, some transracial adoptive parents have found it useful to prioritize their child's culture over their own. For example, interviewers in one study (Pohl & Harris, 1992) quote one transracial adoptive mother as explaining: "I made a conscious decision to live where I would be in the minority and my children would be in the majority" (p. 23). Thus, rather than simply exposing transculturally adopted children to various cultural events, adoptive parents can be encouraged to immerse themselves fully in their child's culture.

David Kirk's suggestion in 1964 that transculturally adoptive families acknowledge the differentness of their members is still relevant today. Notice the European American adoptive mother's description of raising two African American children: "I would go to war

against a racist comment. I would never accept an insensitive comment at school or anywhere. People must begin to respect the norms and values of other cultures ... We're not trying to blend the cultures, but to be happy with the differences and with the different cultures"

(Pohl & Harris, 1992, p. 96). Among transculturally adopted persons, identification with the culture of origin is consistently found to be associated positively with adjustment to and satisfaction with their adoption (see Hollingsworth, 1998).

During the identity-development phase of adolescence, persons in closed adoptions (where the birth parent is not known to the child) may think about, and later search for, their birthparents. The search for birthparents may be a way of resolving the sense of loss attributed to

adoptees (Verrier, 1993) and of integrating their adoptive and birth identities.

Groups now exist that assist adoplees in searching for their birthparents in the United States and abroad, and some domestic adoption agencies can help with accessing adoption records. Searching can be discouraging and threatening to adoptive parents who may interpret

it as an indication of their child's lack of love or loyalty; this is seldom the case. Ninety-five percent of transculturally adopted persons whose interviews were published in the media between 1986 and 1996 said they had a positive relationship with their adoptive parents

(Hollingsworth, 2002). Social workers can help families prepare for the eventuality of a search and communicate openly about it. Adopted persons may also need assistance in coping with the ambivalence of considering a search and with successful and unsuccessful outcomes.

Finally, social workers should be aware of the social context surrounding adoption. Most children become available for adoption as a direct or indirect result of poverty or oppression and the inability of their biological parents to persist in parenting them. The risk of child maltreatment has been found to be eighty percent higher in single-parent families compared to two-parent families, at least twenty-two times more likely in families with incomes below $15,000 compared to those with incomes above $30,000 and three times greater in the

largest families compared to single-child families (Sedlak & Broadhurst, 1996). Socioeconomic factors are particularly implicated in child neglect.

Women in developing countries who abandon their children most often do so in a way that the children will be taken and cared for. And while some overseas orphanages lack the resources to provide other than minimal care, others are quite nurturing and provide a safe and supportive alternative for children whose birth fa milies cannot care for them. This knowledge can help parents in both open and confidential adoptions develop an attitude of empathy, compassion, and respect toward their child's birth parents and those who provided interim care, and convey that to their child. Adoptive parents and adopted persons can be assisted in advocating for conditions in developing countries and in the United States that improve the well-being of families and reduce the necessity for their disruption.

-Leslie Doty Hollingsworth, PhD, ACSW, CSW, is an Associate Professor in the School of Social Work.