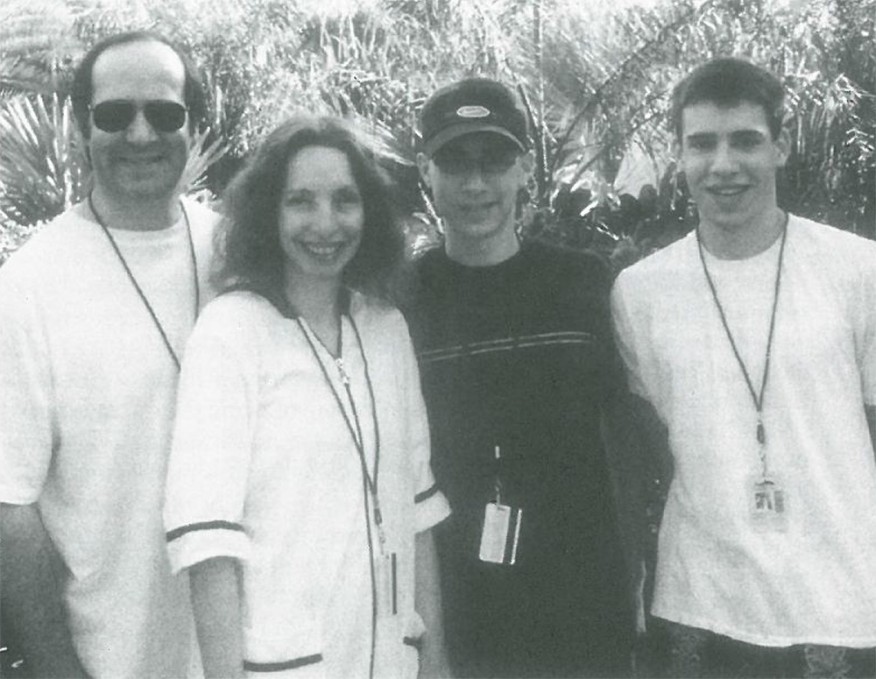

Rhea Braslow earned her M.S.W. in 1976, after growing up in New York City and earning her undergraduate degree at Queens College (City University of New York). Braslow now calls Vernon Hills, Illinois, home, where she lives with her husband, Richard, and their two sons-Andrew is in the Biomedical Engineering program at UM, and Matthew attends Vernon Hills High School.

"All the great group work people were at Michigan, and I wanted to study group work, so I chose Michigan. I still use the Michigan Model techniques to plan activities to meet student goals and focus on a cognitive behavioral approach that has its roots in classes I took at UM." She cites Emeriti Professors Harvey Bencher and Sallie Churchill as mentors who most impacted her growth as a social worker.

Braslow works for the Special Education District of Lake County (SEDOL), a cooperative that includes schools from 37 districts. The co-op rents space in schools in the county to work with children through high school who have special needs due to physical, developmental, and behavioral disabilities. In addition to offering classroom-based services, SEDOL operates four unique schools for hearing impaired, profoundly medically impaired, and behavior disordered students.

Braslow says, "I didn't start my career with a calling toward special ed-it found me. When I returned to New York after receiving my M.S.W., Geraldo Rivera's exposes on the atrocities at the Willowbrook Developmental Center in Staten Island led the State of New York to require state developmental centers to hire Masters-level social workers." A friend was working at a developmental center on Long Island, which afforded Braslow a network through which she began to work at Suffolk Development Center's foster program on Long Island. When she relocated to Chicago, she was hired as a resident services director for the Riverside Foundation, a community residential program for developmentally disabled adults. After having her first child, she decided that the evening and weekend hours that the job demanded were no longer feas ible. She had had contact with SEDOL social workers as they were looking for residential programs for their graduating students, and called them.

Braslow enjoys her work immensely, in part due to the varied nature of her responsibilities. "I work with students on their Individual Education Plans (IEPs), and do direct service kinds of tasks in the classroom including group and individual therapy. I also work with the parents helping them find community services and deal with behavior at home. I also offer them general support and advocacy. It's hard to learn to negotiate the system to find the services you need."

Working for SEDOL is collaborative, too, and there is a certain freedom in being able to try out different techniques in order to meet the IEP goals. She notes that "I never know what kinds of students I'm going to have-this year, I'm collaborating with speech therapists, because in one of my classrooms the children are primarily nonverbal, autistic, or have limited language skills."

While the IEP is a federal document, how progress is charted is not dictated. Over the past five years, Braslow has been involved with developing accountability measures, as well as collecting data and communicating with parents regarding their children's progress and how it is tracked. She's also been spending more time mentoring new employees when they join the staff.

She works with the SEDOL Foundation, a group that raises funds to help families in the school districts that SEDOL serves purchase durable medical equipment, send their kids who have special needs to summer camp, and generally assist with purchases that are beyond the capabilities of parents or school districts. She's part of the team that distributes those funds. This year, they had $40,000 to distribute. Says Braslow, "some years it's very difficult when we don't have enough money, and we have to pick and choose what will be purchased. Medical and therapy bills for the kids are so high that there's often not enough left for parents to do special things for their children, and this is another way that we offer support to families.

"My training at Michigan was very important to my career," she says. "Besides developing a general philosophy about how to approach social work as a profession, my training in group work is something I use every day with students, colleagues, and parents. Now that my children are older and I have reached middle age, I feel ready to devote more time to my interest, and the School is definitely one of them! ")'

Written by Terri D. Torkko