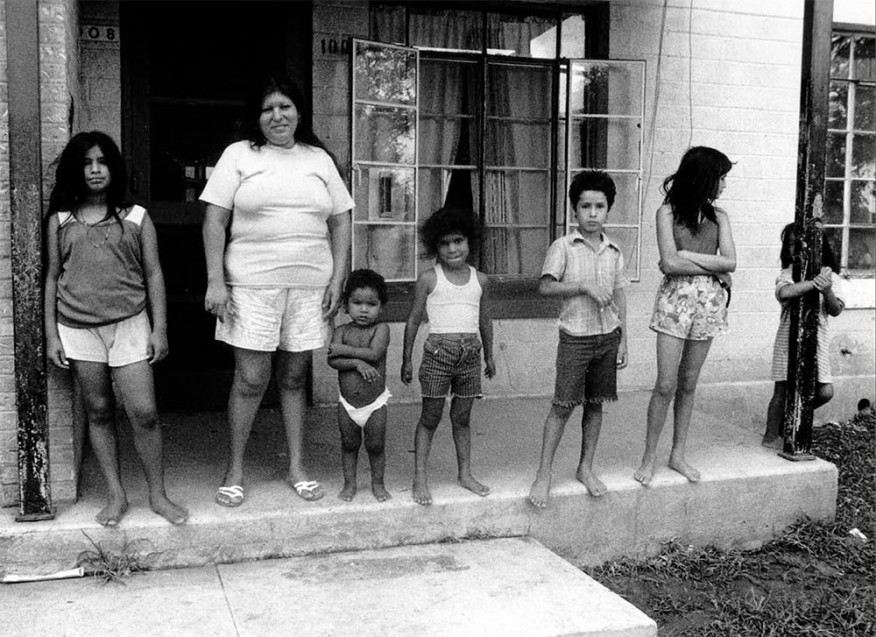

As a case study of the 1996 reforms aimed at moving people from welfare to work, Sarah at first seems a shining example of success.

After her husband left her and their four children, Sarah applied to the government’s Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). About a year later, she was able to find work as a certified nurse’s assistant and leave welfare behind.

But soon after, she lost her house. Despite 12-hour shifts and 50- to 60-hour work weeks, she has not saved enough to lease an apartment. Instead, Sarah and her children have been living with relatives and friends. Her pay, averaging $6 per hour after taxes, goes toward food in the households where they are staying. They move every two or three weeks, because, as Sarah explains, “You don’t want to wear out your welcome.”

Lacking a permanent address has made it impossible for the Texas mother to receive mail or apply for even minimal transitional benefits such as Medicaid and subsidized child care. She applied for Women, Infants, and Children food benefits for her threeyear-old, but her work schedule did not allow her to attend the required nutrition education program. The benefits were denied.

Without medical insurance until she had worked for six months, Sarah postponed shots, physicals, and treatments for one child’s asthma and another’s sinus infection.

“Can I at least have emergency food stamps?” she asked a caseworker.

“As long as you’re working, you’re not classified as an emergency,” was the response.

Dispelling the Myths

Sarah’s story is excerpted from Life after Welfare: Reform and the Persistence of Poverty (2007), Dean Laura Lein’s latest book addressing the interface between families in poverty and the institutions that serve them. The work follows the experiences of 179 families in Texas, where Lein held a dual appointment in social work and anthropology at the University of Texas at Austin before coming to Michigan.

“Texas has been an interesting state to study, because it ranks close to the bottom of the fifty states in its welfare payments and at the high end in proportion of people without health insurance. So it has high rates of poverty, many individuals with untreated medical conditions, and high levels of virtual homelessness,” she says.

The 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act sought to drastically reduce the welfare rolls, and it was undeniably successful at doing so, at least in the short term. “But if the goal was to reduce poverty and increase the well-being and stability of the families who left welfare,” Lein states, “the results are far more complicated and disturbing.”

Her in-depth interviews with “Sarah” (not her real name) and others derive from her training as a social anthropologist. Lein has always been fascinated by “the story behind the numbers.” Writing her dissertation about migrant laborers deepened her commitment to exploring and improving the policies and programs affecting families in poverty. She has studied the welfare system at the state and federal level and its implications for many indigent populations, including immigrant workers, panhandlers, and Hurricane Katrina evacuees, as well as welfare leavers and lowwage workers.

“All of these groups face the same conundrum: a complicated service system based on confusing eligibility criteria and often delivering only a fraction of what’s needed to become stable and selfsufficient,” Lein reports. “They confront numerous barriers to employment and often live in poverty even when employed, all in the context of a flawed services safety net.

“Family stability rests on a four-legged stool: one leg is a living wage job; a second, affordable child care for families with children; a third is health care coverage; and the fourth is affordable housing. Families who have left the welfare rolls without long-term supports in these areas experience marginally increased income but are likely to remain in poverty.”

Needs Beyond “Getting a Job”

Professor Sandra Danziger’s research interests and findings are in sync with Laura Lein’s. A sociologist, she has studied welfare clients and programs since the 1970s. When the 1996 reforms were enacted, she set out to learn how these families would fare in the welfare-to-work transition.

The answer is: not so well. Many women, in particular, have fallen through the cracks.

“Studies throughout the country showed that caseloads plummeted. In one survey of Michigan welfare recipients at the start of the reforms, U-M researchers found that the number of women, mostly single mothers, receiving welfare declined from 72 percent in 1997 to 18 percent in 2003,” she reported.

Danziger noticed the trend that more women each year earned no income and received no benefits. “Disconnected” women in the survey rose from 1 percent in 1997 to 8.6 percent in 2003. She has documented their barriers to employment, including learning disabilities, less than high school education, alcohol or drug dependence, lack of work experience, and health problems in both the parents and children.

What troubles her about these unemployed and unsupported women is that “they have profoundly complicated lives. With low education, physical and mental health problems, and minimal skills, they are living on the edge. With no stable income, they may be living with friends or relatives. The more barriers a woman faces, the less likely she is able to maintain stable employment.”

On a positive note, Michigan’s welfare-to-work program is becoming more flexible, she noted. “So instead of a minimum wage job, some clients are being offered training for higher-wage professions like truck driver or nurse’s aide.”

But she would like to see the focus go beyond “getting a job,” to address the physical, mental, and emotional issues that hold many people back. “For example, a welfare recipient who is diagnosed with depression could be exempted from work while she pursues counseling,” Danziger suggests. “Or counseling could be counted as one of the required activities for maintaining benefits while seeking a job.”

Denying access to Unemployment

Of course, “getting a job” does not guarantee a transition from poverty. Assistant Professor Luke Shaefer notes that in the United States, employers are often expected to provide benefits like paid sick leave, maternity leave, and pensions. Workers in the lowest quintile, making $12 or less per hour, are rarely offered these options.

He sees an improvement in one piece of Laura Lein’s four-legged stool: “Public health insurance for children of poor families has expanded from 18 million in 1987 to 30 million in 2007,” he reports. The increase is due primarily to expanded eligibility for Medicaid, especially under the creation in 1997 of the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP).

But while the families of more low-wage earners are being covered by health insurance, he says that few are being protected by unemployment insurance.

“It’s a complicated program, but there are two main eligibility elements. First, the worker has to have earned a certain amount in the past year, and the large majority of low-wage workers actually meets their state’s monetary requirements. The second relates to the terms of the job separation. If a worker quits voluntarily or is discharged for cause, most states will not grant unemployment benefits.

“Most low-wage jobs don’t lay people off,” Shaefer explains. “They just cut hours or change schedules, making their lives unpredictable.”

He envisions a system where workers are allowed to “bank” months of unemployment insurance and draw upon it when needed—“enabling a woman to extend her maternity leave or a manufacturer to use a year’s worth to return to school and get retrained. Someone who never left a job could draw upon it after retirement.”

Employment issues also interest Associate Professor Sherrie Kossoudji, especially as they relate to immigrants. Her research compares the experiences of three groups: immigrants who have become citizens, immigrants who aren’t citizens but have legal status (green cards), and illegal immigrants.

An economist, Kossoudji looks at whether there are issues associated with being an immigrant that affect income parity. How much lower are their wages? How much more likely are they to live in poverty?

“Following the reforms of 1996, undocumented immigrants have been ineligible to receive welfare. These workers do have labor rights, but to claim these rights, they must admit they are here without papers,” she points out.

“It is a real catch-22. And it raises an ethical conundrum. People talk about how illegal immigrants use our resources but not how we benefit from their presence. Prices are lower because of their labor. Is it ethical for us to eat cheap strawberries while denying them services?”

* * *

If the reforms of the past decade seem to have promoted as many problems as progress, the U-M SSW researchers are intent on the possibilities for future changes and developments in poverty policies and programs.

“The strengths and resilience that so many families draw on to face the exigencies of poverty can be developed and supported by new ventures developed through research and evaluation on new types of approaches,” Dean Laura Lein says. “Focused research and the development of model programs can influence policymakers and the larger public as well.”

—Pat Materka, a former U-M staff member, is a freelance writer who owns and operates the Ann Arbor Bed and Breakfast.