In July 1940, after years of research and design, the State of Washington proudly opened the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, creating a valuable link bwteen the Olympic Peninsula and the Washington mainland. Four months later, the bridge, subject to swaying rhythmically in even minor winds, began violent undulations. By 11 a.m. on the morning of November 7, 1940, most of the span lay on the floor of Tacoma Narrows, its side spans, with no support, sagged despondently in the wake of the disaster.

What, if anything, could have saved the bridge that was lovingly called "Galloping Gertie?" The simple answer is research. The man who initially designed the bridge wanted to create an elegant strand, gracefully reaching between land masses. Unfortunately, it was this design that caught the wind like a large cement wing instead of shrugging it off. The builders simply did not understand the aerodynamics or design principles that would allow a light, airy structure to stand strong in a breeze. Reseraching those scientific principles would have produced useful evidence about how (or how not) to build a bridge. A new Tacoma Narrows bridge opend approximately 10 years after Gertie collapsed. The new bridge, now called "Sturdy Gertie" stands today, due in no small part to the premier instance of a resesarch progarm implemented to investigate the aerodynamic effects of wind acting upon a bridge.

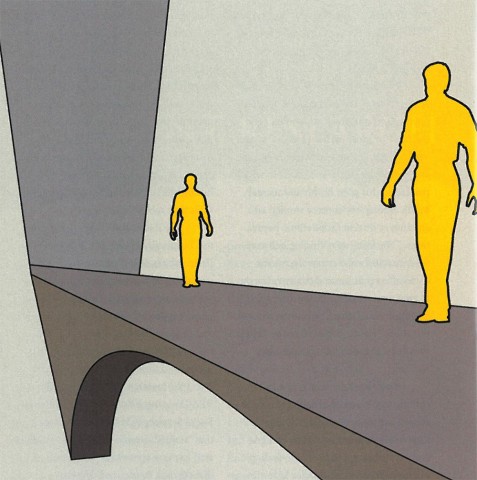

So what does a bridge in Washington State have to do with the profession of social work? If we view the bridge in its reality, it means nothing; if we see it as metaphor, it means everything. In the absence of evidence-based research to undergird social work practice and policy, we, too, could be contributing in negative and harmful ways to those we desire to help.

Like other schools of social work, we aspire to generate scientific/empirical evidence to promote the well-being of individuals, families, communities and organizations. Our charge is to generate research and translate it into practical application for consumption by students and other relevant groups/readerships. The very same thing that led to a more enduring Tacoma Narrows bridge-researchwill provide the link between academia and practice.

The movement toward evidence-based practice is an evolution of the field of social work. During the early years of social work and social work research, examining practice meant looking "outward at social conditions" rather than looking "inward at the profession's own interventions" (Mullen, 2002). As both the world and the role of the social worker expanded, particularly in the politically charged 1960s and 1970s, an emerging research field started providing more answers about the effectiveness of traditional social work interventions (Mullen, 2002). The scope of social work research has continued to expand. We now find ourselves playing more roles, assisting more diverse populations and organizations and working in countries that had not previously been on America's radar, creating a need for research.

After years of moving towards evidence-based research, social work's time has finally come. This evidence-based movement is gaining support and recognition among important external organizations. In May 2003, the National Institutes for Health published the NIH Plan for Social Work Research. As requested by Congress, the plan, the first for NIH," ... outlines research priorities, as well as a research agenda, across NIH Institutes and Centers ... " (Senate Report 107-216, p. 155). According to the published report the plan calls for:

1. Establishment of a social work research committee, convened to monitor the state of affairs in the field of social work research as it relates to health and the NIH research agenda.

2. Expanded outreach activities to encourage the submission of investigator initiated research projects focused on studies of social work practice and concepts relevant to missions of each of the NIH Institutes.

3. Proposal of a new Program Announcement entitled "Developmental Research on Social Work Practice and Concepts in Health" to provide the impetus and resources to fully incorporate social work's unique concepts and perspectives into the NIH research portfolio and to build the scientific base to be used by allied health professionals.

4. Implementation of a competitive supplement for current Research Project (RO 1) grantees patterned after the minority supplement mechanism. Social work researchers would be added to existing research projects to increase mentoring, research training and improve competitiveness for NIH funding.

5. Development and implementation of an NIH Summer Institute of Social Work Research offering new researchers intensive exposure to issues and challenges in the field of social work research.

6. Planning a meeting at NIH, involving all interested ICs and an invited group of deans from schools of social work with doctoral programs to explore the needs of the social work research community and share information about the NIH grant process, areas of research appropriate for social work researchers, and the kind of faculty support needed in order to successfully apply for and conduct NIH funded research.

7. Exploration of the possibility of a joint effort between NIH and social work research organizations to host a conference on the topic of advancing the social work research agenda.

8. Planning a trans-NIH conference highlighting social work research results relevant to health.

9. Development and implementation of coordinated outreach efforts to universities that would include training on writing grants and provide information about research opportunities.

Although considerable details are needed to launch this plan fully the push by NIH to include social work research comes as no surprise. Research has shown that social conditions, poverty, the environment and other factors affect the mental and physical state of the individual, as well as community health. Formally calling for collaboration demonstrates that NIH recognizes the significant role of the profession of social work. This support will facilitate the movement toward more evidence-based research in our field, which will mirror the emphasis on evidence-based research in the medical, nursing and public health fields. As consumers, we rely on the evidence from medical research, knowing that it shapes not only best practice in medical care, but medical education and health care policy.

Our challenge is to develop a milieu within our School that leads to an appreciation and true interest in research among our students. Opportunities to engage our students in the research enterprise as a critical part of their educational preparation is vital.

The School has converted internal and external funding dollars into research opportunities for students. In the fall of 2003,91 M.S.W. students were involved directly in research projects, the benefits of which often create unique opportunities for increasing the students' appreciation for research as well as building an undergirding for their practice.

Professor Michael Spencer, Co-Investigator of the SSW Family Development Project, states," ... [F]or many of the students who work with me, it's an opportunity to be exposed to the research process. Many of them don't really know what research entails and don't think about a career in this area, but then consider [it] once being exposed." In addition to prompting interest in professional research paths, Spencer thinks that research experience opens up the possibilities of different interest and practice areas. "I think in the area of health and child development, students who come to me are typically interested in these areas. Other students have come to me with interests in other areas, but then start to develop interests in [health and child development]. It also provides them with additional knowledge of the literature that they might not get in classes, assessment tools and some knowledge of evaluation all in the context of real life settings [such as community-based research]."

Adjunct lecturer Sallie Foley ('78) has taught Grief and Loss for 23 years, in addition to her work as a Senior Clinical Social Worker (ACSW) at the U-M Medical Center, where she is responsible for the provision of outpatient psychotherapy services, and her private practice in psychotherapy and consultation. "The practice of social work, either as clinician or teacher, is based upon an understanding of theory and research," she says.

Foley is also an AASECT certified sex therapist and sex educator and writes and speaks frequently on the subject of human sexuality. "The teaching of and treatments for sexual difficulties are excellent examples of the need for research-based practice. Sexual problems have a biopsychosocial basis that requires a strong understanding of research both in physiologic and pharmacologic developments and in advances in clinical practice."

She observes that clinical practice has changed dramatically over the last quarter century, in large part due to ongoing research and its practical application. "In the 1970s, we believed and taught that autism was caused by cold, unfeeling parents. We now know, based on brain research and clinical study, that autism is a communication disorder and is biologically based."

During her time as an instructor of Grief and Loss, she has seen "tremendous shifts in our understanding based on research related especially to trauma, family systems, poverty and social injustice.

"Direct clinical practice is continually in dialogue with research, both on clinical methods and on biologic and sociologic underpinnings for many problems seen in practice. Without a grasp of what research is telling us, I would not be effective either as a clinician or teacher."

-Paula Allen-Meares is Dean and Norma Radin Collegiate Professor of Social Work. Melissa Wiersema is special projects coordinator for the School of Social Work.