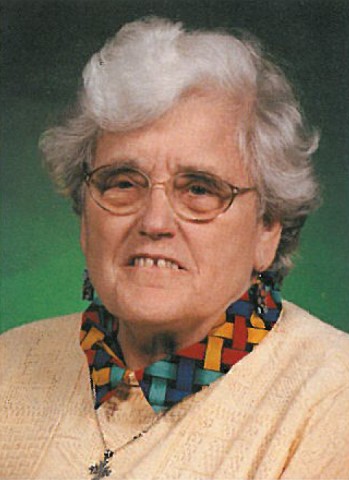

When Sallie Churchill retired in 1995, the School invited alumni and colleagues to contribute memories for a book to be presented to her. An avalanche of cards, letters and even poems was submitted, testifying to her stature as a beloved professor. In turn, Churchill demonstrated her affection for her students by suggesting that donations in her honor be made to the School's Student Emergency Aid Fund.

Initially a chemistry major and math minor at the University of Minnesota, Churchill took a sociology course that had a sequence in pre-social work. Placements at a settlement house, residential treatment center and child guidance clinic convinced her to continue her studies in social work, focusing on children. Following completion of her MSW at Minnesota, she worked at the Pittsburgh Child Guidance Center with emotionally disturbed children, at a treatment home for African American teenage women and taught group process at a University of Pittsburgh program for child-care workers.

Her work and research with children, particularly those adopted or in foster care settings, were gaining a national reputation. In 1962, she was invited to speak at the Michigan Child Guidance Center on group work with children. Churchill joined the SSW faculty shortly thereafter, enhancing the already distinguished group work program. She recalls, "I didn't think anything could replace the pleasure of group work, but teaching did. I found a population at the School in Social Work that was as wonderful as the children I had worked with."

After three years, Churchill left to attend the Ph.D. program at the University of Chicago. She said she would "finish in three years, or quit;" her orals took place after three years and one day. Dean Fedele Fauri contacted Churchill as she was completing her degree to find out when she was returning, which amazed her, because she had resigned before starting her studies in Chicago. She returned to the School in 1970 and plunged back into teaching, supervision, research and liaison work with her characteristic enthusiasm and energy.

According to colleague Sheila Feld, as a teacher Churchill was "very knowledgeable about her subject matter, from both conceptual and practical perspectives. I was always impressed with how deeply she thought about pedagogy and how innovative she was in trying to organize her classes and behavior in ways that would reach the students." When teaching supervision, Churchill admitted to using behavior modification techniques that she had figured out when working with troubled children. She enjoyed being a liaison and visiting agencies so that she could help them improve their service delivery to children. Churchill wrote several important articles on group work and adoption, and edited No Child Is Unadoptable.

She credits her student Kathleen Faller, now a professor at the School, with piquing her interest in child abuse and neglect that dominated the last ten years of her career. Faller recalls, "In 1985, I asked her to consult with the Family Assessment Clinic, and we worked together until she retired. She provided assessment services, did treatment, mentored MSW and doctoral students and testified in court. One of the remarkable things about Churchill as a social work professor is that she always had her priorities right-first clients, second students, and third her own advancement. Because of this, her career was quite remarkable and should be a model for us all."

Churchill also has a strong sense of service. At the School, she coordinated the Interpersonal Practice Program and served on the Executive Committee. She also served on many nonprofit boards, including as president of SAFE House in Ann Arbor. Most recently, the U-M Medical School appointed her to the Washtenaw County Health Organization Board. She was honored for her service to the School of Social Work in 1995 when she was given the Distinguished Faculty Award by the Alumni Board of Governors.

According to colleague Charles Garvin, "Churchill stood steadfastly for several things that made her, at times, the conscience of the School. She stood for an emphasis on defining and teaching good practice, which she based on her many years of working with individuals and groups. She was rightly skeptical of research that did not in some way lead to better service to people. And she was always ready to reach out to students and faculty when they experienced personal crises."

In retirement, Churchill has made a clean break from academia and devoted her energies to her church, friends and travel. When asked what she misses most, she answered simply: "the students."

- Robin Adelson Little is a freelance writer living in Ann Arbor. She is a past editor of Ongoing.